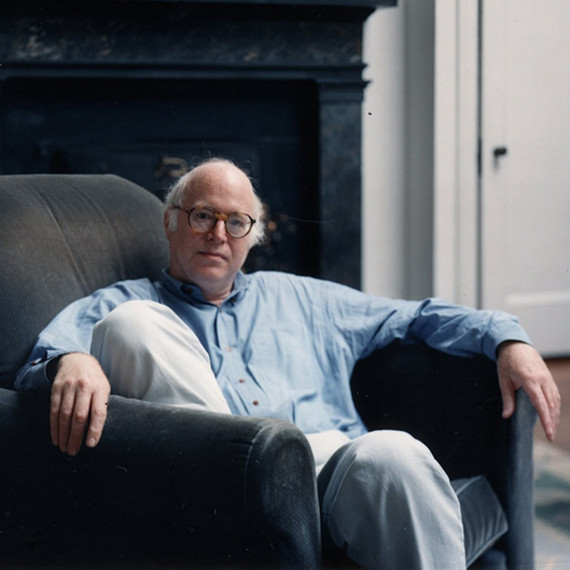

Interview with Richard Sennett

The American sociologist Richard Sennett has studied the topic of urban living and community for over thirty years. In an interview he talks about the perils and possibilities of more open, porous forms of urban planning and communal living.

You have written extensively about the concept of the »Open City«. What is wrong with conventional urban planning?

In 1990 I was in the office of an urban planner in Berlin. He had a huge model on the table. At one point he unveiled it and said: Look here, this is the new Alexanderplatz, already finished! Of course his plan was completely undemocratic – he just wanted to put a finished model on top of the city district. That is possible in modern capitalism, but it doesn’t involve the people that are affected. The urban planner who believes he has a solution for every problem is the source of all ills. Moreover, authorities tend to only build what is already familiar to them. And many architects are reluctant to collaborate with residents during the design process.

Does urban planning also fail because capitalism places no value on community?

Yes, of course. Investors and investment companies typically know almost nothing about the area in which they are building. The situation is further exacerbated by ›flipping‹: one investor begins to build and then sells their stake in the project before the structure is completed. There should be a law mandating that every investor in a new building must hold their share in the property for a minimum of three years – yet even raising the issue has incited protest among investors: We can’t work that way!

From your perspective as a sociologist, what does the perfect dwelling look like?

That is exactly the kind of question that demands a closed, over-determined answer, a finished plan – but it would be much more helpful to adopt a new way of thinking, a non-linear and open approach that allows for unfinished spaces.

Okay, then what characteristics should a good dwelling have?

It would have a flexible, unfinished form with space for more – or less – interaction. The inhabitants should be able to modify the individual spaces and rooms at any time. In that regard, the eighteenth-century English townhouses designed for large extended families are very flexible. They resemble a shoebox: interior walls can be easily moved, and today the rooms are multifunctional. The simplicity of the form facilitates flexibility.

Isn’t the family structure also very closed, in comparison to a group of people who share a flat?

The concept of the nuclear family might be similar to a gated community, but with a divorce rate of 50 percent, with completely new family structures like same-sex couples, the family has long ceased to be a closed system.

Germany now has more single-person households than small families or shared flats.

Yes, but people who live alone go out more often, go shopping, frequent bars and restaurants. The only singles who inevitably suffer from loneliness are the elderly.

What will residential living look like in the future?

I am searching for new forms of living – not shared flats, but houses that enable communal living in a larger context and encourage the creation of public spaces. My colleagues and I want to re-invent the urban residential block, providing public spaces that work without intruding on the privacy of the individual. With communal gardens and enough space for children, who could be alternately supervised by neighbours. The trend towards living alone has proved to be negative. For someone in their twenties, it’s fine to live in a sublet. But it would be better if people could live together and contribute to the community. And if private and public spaces were more porous.

Richard Sennett is one of the most acclaimed sociologists of our time. He writes about cities, labour and culture, and teaches sociology at New York University and the London School of Economics. His most recent publications are »Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation« (2012) and »The Open City« (2016). A longer version of this interview, conducted by Thomas Bärnthaler und Lars Reichardt, appeared in the Sueddeutsche Zeitung Magazin.